Acclimatization and altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro

Acclimatization and Altitude Sickness on Kilimanjaro – High altitude trekking comes with obvious risks – Advice on how to cope with changing altitude.

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) (aka altitude sickness or altitude illness) and its severe variants, High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) and High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), are your biggest concerns on Mount Kilimanjaro.

On this page we have provided an overview on the process of acclimatization and Altitude Sickness on Kilimanjaro, as well as detailed information on the types of altitude sickness symptoms you might experience on your trek.

We have also included information on preventative medications like Diamox.

The information on this page has been gathered from various sources but we are particularly indebted to Rick Curtis’ Outdoor Action Guide to High Altitude, written for Princeton University, and recent insight from the Everest Base Camp Medical Centre.

PLEASE NOTE:

The information in this section, as with the whole website, is provided as an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. The information is not intended to be patient education, does not create any patient-physician relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. Research in this area is always progressing which may mean some of this information is out of date. It is your responsibility to seek the latest information should you be going to high altitude.

ACCLIMATIZATION ON KILIMANJARO – INTRODUCTION

Acclimatization is the process by which the body becomes accustomed to lower availability of oxygen in the air and can only be achieved by spending time at various levels of altitude before progressing higher.

Oxygen, Air Density and Altitude

Acclimatization is best understood by looking at the relationship between oxygen in the air, air density and altitude changes.

At sea level oxygen accounts for about 21% of air and barometric pressure is around 760 mmHg (millilitres of mercury). As one climbs in altitude the amount of oxygen in the air remains about the same (up to approximately 21,000 meters or 69,000 feet), however, air density drops and thus less pressure is put on packing oxygen molecules closer together (imagine oxygen molecules moving further and further away as altitude increases).

For example, at about 3,600 meters (12,000 feet), barometric pressure is around 480 mmHg. With less air density, oxygen molecules are more widely dispersed in any given column of air and hence less oxygen is available per breath.

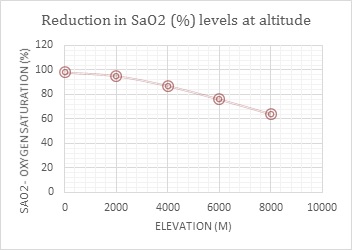

Blood oxygen saturation

The body deals with this decrease in available oxygen by breathing faster and deeper (even at rest) so as to increase the oxygen content in the blood (i.e. blood oxygen saturation or SO2).

The chart below shows the typical profile of oxygen saturation in an average person’s blood as one ascends to higher altitudes. For the average person, you can see that blood oxygen saturation (SO2) decreases to nearly 80% at 6,000m (just above Kilimanjaro’s summit).

Kilimanjaro Altitude Zones

On Kilimanjaro there are three altitude zones – high altitude (2,500 – 3,500 metres), very high altitude (3,500 – 5,500 metres) and extreme altitude (above 5,500 metres).

Most people can ascend to 2,400 meters without experiencing the negative effects of altitude. However, as one enters the high altitude zone changes in air density and available oxygen begin to impact one’s physiology.

One’s susceptibility to these changes is very difficult to predict, though, as there is very little correlation to factors of gender, age, fitness etc.

We do however know that going too high, too fast is the key cause of AMS. Other contributing factors are dehydration and over exertion at altitude.

A proper acclimatization strategy involves not going too high, too fast whilst also ensuring you don’t overexert yourself and remain well hydrated.

To illustrate this point it is worth thinking about a term that climbers call the acclimatization line.

Acclimatization Line

The term is used to describe a point at which someone’s altitude sickness symptoms occur.

For example, let’s say a person’s acclimatization line is 3,000 metres on day one. After trekking to this height and spending a night or two there, the body would acclimatize to that altitude and that person’s line might move to 3,800 metres. If they then climb to 3,700 metres they will remain asymptomatic, but if they climb to 4,000 metres they would begin to experience altitude sickness symptoms.

Very near to one’s acclimatization line the body can continue to adjust and a day or two’s rest at that height will usually result in the resolution of symptoms. However if one continues to ascend beyond ones acclimatization line it is almost guaranteed that symptoms will worsen and further acclimatization will not occur. It is critical that one gets below the point where symptoms began in order to see improvement.

This last point illustrates why it is so dangerous to ascend with any symptoms of altitude sickness.

How the body adapts to higher altitudes

Here’s the good news – your body is very good at adapting to changes in its environment. Given enough time your body can adapt to high altitude. Four main body changes are worth mentioning. As you ascend:

1. Breathing becomes a lot deeper and faster

2. Red blood cell count increases which allows more oxygen to be carried in the blood

3. Pressure in your pulmonary capillaries increases which forces blood into areas of the lungs that are not used when breathing at sea level

4. More of a particular enzyme is produced which causes oxygen to be released from hemoglobin to the blood tissue

It is important to remember that your body can cope at altitude, it just needstime to acclimatize.

ACUTE MOUNTAIN SICKNESS (AMS)

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) – also know as altitude sickness and altitude illness – is a pathological effect on humans caused by going to high altitudes too fast, where lower levels in oxygen inhibit normal physiological processes.

People typically start experiencing Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms at about 10,000 feet (3,000 m).

Some people can experience symptoms as low as 8,000 feet (just over 2,400 m).

Due to Kilimanjaro’s rather rapid ascent profile, altitude sickness amongest trekkers is unfortunately quite common.

There are three levels of Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms – mild, moderate and serious. We discuss each here.

Mild Symptoms

These include:

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Nausea and Dizziness

- Shortness of breath

- Disturbed sleep

- Loss of appetite

If you suffer any of the symptoms above it is important to communicate to your climbing partners and guide how you are feeling. These symptoms generally disappear if you rest for a day at the level at which they originally started. This is why an acclimatization day where you climb high and sleep low is so important!

Moderate Symptoms

These include:

- Very bad headaches that is not relieved with medication

- Feeling very nauseous which often resulting in vomiting

- Very fatigued and weak

- Decreased coordination (known as ataxia)

- Shortness of breath

A clear sign that you are experiencing moderate altitude sickness symptoms is when one or all of the mild symptoms start getting worse to a degree that becomes debilitating. Typically people experiencing moderate symptoms have very bad headaches and usually vomit. A feeling of decreased coordination is common (i.e. ataxia).

People can often walk on their own when experiencing moderate AMS, however ascent under such symptoms will almost certainly result in worsening of the symptoms to a degree where one cannot walk anymore. This would necessitate a stretcher evacuation, which should be avoided at all costs.

Ascending under moderate symptoms can lead to death.

It is important you descend at least 1000 feet (300m), but more if necessary, and remain at a lower altitude until the symptoms subside. Once the symptoms have disappeared you have acclimatized and you can ascend again.

Serious or Severe Symptoms

These include:

- Inability to walk

- Shortness of breath whilst resting

- Loss of mental capacities and hallucination

- Fluid build up on the lungs

Ascent under serious Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms is extremely dangerous and should never occur. People experiencing serious AMS are usually unable to walk, struggle to breathe and lack their mental capacities to think straight.

There are two conditions associated with serious AMS, each of which occurs when fluid leaks through the capillary walls either into the lungs (this is called High Altitude Pulmonary Edema – HAPE) or into the brain (this is call High Altitude Cerebral Edema – HACE).

Both conditions are rare but almost always occur because of ascending too high, too fast, or because one has stayed too long at very high altitude. We discuss each here:

HIGH ALTITUDE CEREBRAL EDEMA

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), is a condition associated with severe Acute Mountain Sickness. It occurs due to swelling of the brain tissue from fluid build up in the cranium. It is a life threatening condition.

On Kilimanjaro, people suffering from HACE should descend immediately and seek medial attention when they get to the lower reaches of the mountain.

HACE can be identified if someone is suffering from the following symptoms:

- Severe headaches which cannot be relieved by medication

- Hallucination

- Loss of consciousness

- Disorientation

- Loss of coordination (i.e. ataxia)

- Memory loss

- Coma

HACE tends to set in at night. Do not hang around until morning if someone in your group is suffering HACE symptoms. The longer you wait at altitude the greater the probability of fatality. Descend immediately – even under darkness. Under no circumstances should one ascend if they have suspected HACE symptoms. If you have oxygen it can be administered along with a steroid called, dexamethasone, but these should only be used in conjunction with rapid descent.

HIGH ALTITUDE PULMONARY EDEMA

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) is a condition associated with Acute Mountain Sickness and occurs because of fluid build up in the lungs.

Fluid in the lungs prevents the effective exchange of oxygen and thus a decrease of oxygen into the bloodstream.

HAPE almost always occurs because of ascending too high, too fast.

It is a life threatening condition and therefore every precaution should be taken to avoid it when trekking Mount Kilimanjaro.

Clear symptoms that one is suffering from HAPE include:

- Very short of breath, even while resting

- Very tight chest

- The feeling of suffocation, particularly while sleeping

- Coughing that brings up white, frothy fluid

- Extreme fatigue and weakness

- Confusion, hallucination and irrational behaviour

If the last symptom occurs (i.e. confusion, hallucination and irrational behaviour) one can assume that the pulmonary edema has started to affect the brain due to a lack of oxygen in the bloodstream.

Any available oxygen should be administered. The drug, Nifedipine, has been shown to ameliorate the condition, but descent is the only cure.

Trekkers should take care to ensure that the person descending with High Altitude Pulmonary Edema doesn’t exert themselves as this can result in worsening of the condition. A stretcher evacuation is the preferred method of descent.

Once the person has reached the lower limits of the mountain, medical support should be sought immediately.

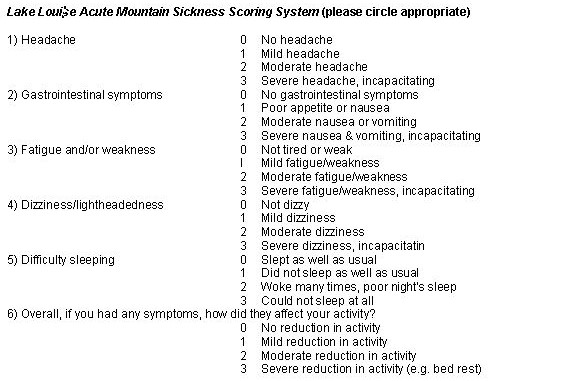

LAKE LOUISE ALTITUDE SICKNESS SCORECARD

There are a number of ways to monitor altitude sickness symptoms. The most common method uses the Lake Louise Altitude Sickness Scorecard (as seen below).

Scores between 3-7 are a sign of mild to moderate AMS. Scores above 7 are a sign of severe altitude sickness.

Reliable Kilimanjaro tour operators will use a combination of the Lake Louise scorecard method and spot oximeter and pulse readings to monitor your performance on the mountain.

If you score over 8 on the Lake Louise scorecard or have an SO2 reading below 75%, it is likely that you will need to forego your summit attempt and descend.

GOLDEN RULES

Trekking the Kilimanjaro need not be a very risky or dangerous adventure as long as you follow some basic rules.

In particular:

- If you have a chance to pre-acclimatize before trekking Mount Kilimanjaro, do so. A good option in Tanzania is to trek the neighboring Mount Meru (4,565 m) before attempting Kilimanjaro

- If you are a novice high altitude trekker then choose a route itinerary that is at least seven days long (6 up, 1 down). In our opinion, the seven day Machame or 7/8 day Lemosho are the most suitable routes for the average trekker

- Ensure the route allows for a good climb high, sleep low opportunity (both the Machame and Lemosho do)

- When on the mountain make a point to go as slowly as possible, do not overexert yourself, even on the lower reaches

- Drink loads of fluid (2.5-4 liters a day)

- Do not drink alcohol, take stimulants, smoke or consume caffeine on the mountain

- We recommend taking acetazolamide (Diamox)

Finally, as recommended by the charity, Altitude.org, always remember these 3 Golden Rules when at altitude:

- If you feel unwell, you have altitude sickness until proven otherwise

- Do not ascend further if you have symptoms of altitude sickness

- If you are getting worse then descend immediately

PREVENTATIVE MEDICATIONS – DIAMOX

Acetazolamide, or Diamox, is a drug that has been proved to be effective at mitigating altitude sickness.

The drug helps to increase the acidity of the blood by acting as a diuretic and promoting urination. Increased acidity in the blood is equated by our bodies as increased CO2, and hence one starts breathing deeper and faster to get rid of the CO2. Deeper, faster breathing increases the amount of oxygen received by the blood and this helps prevent the onset of AMS symptoms.

It is important to note that Diamox is a prophylactic (preventative medicine), and does not cure the symptoms of AMS. Once altitude sickness symptoms have started, the only way to stop them is descent. Under no circumstances should Diamox be used to continue an ascent with AMS.

Diamox is also a prescription drug so it is important that you first consult your doctor to check whether it is a suitable drug given your particular medical history. It is not suitable for pregnant women or anyone with kidney or liver disease issues.

We recommend taking Diamox for 2-3 days 2 weeks before departure to test whether you experience any side effects.

Typical side effects associated with Diamox are:

- Frequent urination – everyone experiences this when taking Diamox. It can result in the development of kidney stones so it is important that you drink loads of fluids whilst taking the medication

- Numbness and tingling in the fingers, toes and face – Many people experience this side effect when taking Diamox. The sensation is a little discomforting but not dangerous

- Taste alterations (some foods might taste weird)

- Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea – this is rare. These side effects should be identified during your test before departing for Kilimanjaro. Unfortunately these side effects are common with AMS and therefore can easily be misdiagnosed as AMS

- Drowsiness and confusion is also possible – again these side effects can be confused with AMS

Diamox comes in 250mg tablets. Most people take half a tablet in the morning and half in the evening. You should start taking tablets one day before arriving in Kilimanjaro and continue taking the same dosage for all ascent days. You can cease taking Diamox on descent.

TREKKING INSURANCE

Due to the risks of altitude sickness and the various other issues that can arise on Kilimanjaro it is worth getting trekking insurance cover. We recommend you visit World Nomads website to get a quote for your cover.

We have also exposed the area that we advise you take insurance for; Read our Kilimanjaro Travel Insurance Advice

READ MORE USEFUL INFORMATION

- Kilimanjaro Routes – Overview.

- Can Anyone Climb Kilimanjaro?

- Best Time to Climb Kilimanjaro.

- Kilimanjaro Travel Insurance – Better Safe than Sorry…!

We hope this article has answered all your questions on acclimatization and altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro. If you have any more questions, feel free to Contact Us.